About

The commons exists, whether we acknowledge it or not.

Into the cave

Every system in which people act together; from teams and institutions to online platforms and global networks, depends on a set of conditions that hold cooperation in place. These conditions are rarely named, rarely measured, and rarely understood. But when they weaken, we notice the consequences immediately: friction, confusion, escalating oversight, rising control.

Most societies respond to these problems with more rules, more process, more structure – all imposed from above. Control feels tangible. It produces immediate motion. But motion is not the same as cooperation, and over time, control becomes expensive and oddly ineffective.

Cooperation is different. It is the architecture underneath collective action: the alignment of meaning, the visibility of behaviour, the commitments that allow people to act without second-guessing one another. When these elements reinforce each other, systems feel light, adaptive, and creative. When they crack, the same systems begin to harden. They defend rather than evolve.

The framework does not tell anyone what to do. It simply reveals the patterns we already live inside.

We feel this everywhere. In strained teams. In institutions unable to adjust to new realities. In political environments where meaning fractures faster than it can be repaired. In online spaces where identity and interpretation are captured by a few actors at extraordinary scale. Worst of all, we feel it everyday when we try to do things together under conditions that feel increasingly fragile.

Yet for all this, cooperation remains almost invisible. We treat it as personality, chemistry, goodwill, or culture. We attribute its failure to the people involved rather than to the structure around them. Lacking a clear way to describe how cooperation works, we default to the one tool we can see: control.

My work began as an attempt to understand this invisibility.

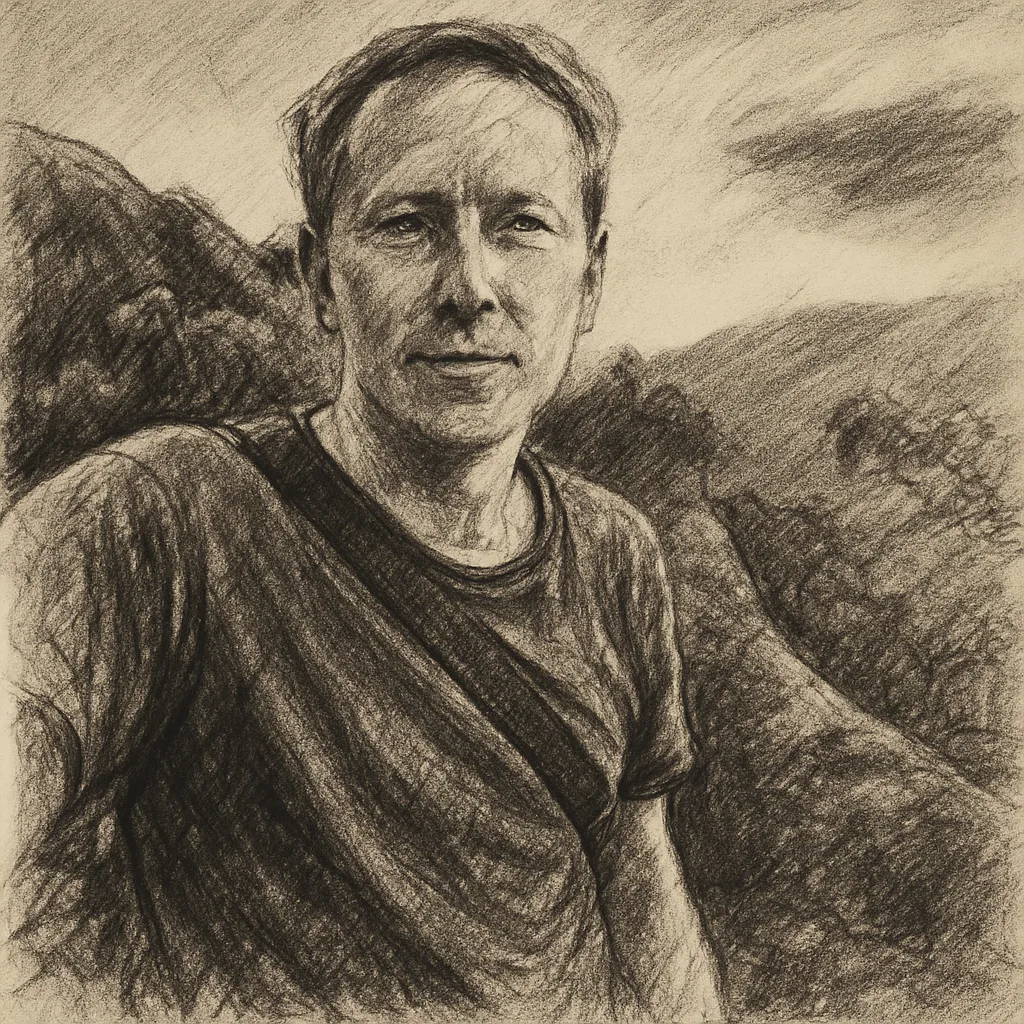

Mike Harris – Founder of Exonym

What made those years difficult wasn’t that others misunderstood the project; it was that I couldn’t even explain what it was.

Long before the framework had a name, I kept encountering systems that behaved in ways I could sense but could not yet articulate. Systems that were cooperative but then decayed – only for cooperation to resurface again later. I guessed it was shaped far more by structure than by intention.

I first learned this in Quality Assurance, where coordination is framed through process and control. If you want good outcomes, you follow the rules; if people resist the rules, you explain the resistance. It took time to see how rigid process reshapes the work beneath it: how it flattens judgement, distorts behaviour, and becomes a proxy for both responsibility and blame. Nothing about that was malicious. It was simply the only lens available.

Around the same time, the large technology platforms were getting larger and it forced a deeper realisation: that meaning, identity, and coordination were being centralised at a scale no institution was prepared for. It wasn’t about founders or about intentions. It was about the structural consequences of holding that much power.

Governments weren’t resisting it; they were seeking it. That moment pushed me toward the deeper problem of identity. Toward how identity systems create hierarchy, collapse feedback loops, and make cooperation fragile.

Across all these environments, one question kept resurfacing: how do you create order that does not rise above the people inside it?

Systems like money, social media, identity, and governance all have a tendency to dominate the people who rely on them. Decentralised rulebooks, the foundation of Exonym became my way of exploring whether systems could be designed differently:

- not authority-less, but authority-distributed;

- not structureless, but structured in a way that remains open to reinterpretation;

- not identity-driven, but reciprocity-driven.

Patience was not optional. Most of the project was spent stumbling in the dark, understanding the behaviour long before I understood the structure. I made designs that were elegant but wrong, and designs that were inelegant but nearly right. I rebuilt commitment models, replaced empowerment hierarchies with self-empowerment, refactored, revised and waited — sometimes for years — for a clearer pattern to emerge.

The work followed me. The puzzle had a kind of gravity. What made those years difficult wasn’t that others misunderstood the project; it was that I couldn’t even explain what it was. I was still in the cave, aware only of its behaviour, not the structure behind it. Until I could see that structure clearly, there was nothing simple to say.

Out of the cave

When it works, cooperation is so natural that it disappears into the background. I didn’t yet recognise it as a system of meaning, visibility, commitments coming together and falling apart. All I knew was that something real was happening in the design, and that it mattered long before I could articulate why.

The Generative Commons is the articulation of what eventually became clear: cooperation has a structure, and that structure explains why it holds and why it collapses.

It explains why trust and niceness emerge rather than cause cooperation. It explains why identity destabilises systems even when everyone involved is well-intentioned. It explains why divergence and difference are not threats but sources of generativity. And it explains why systems fail when control replaces meaning, visibility, and commitments.

The framework does not tell anyone what to do. It simply reveals the patterns we already live inside. The patterns that become visible once you stop looking at individuals and start looking at the structure that surrounds them.

I study the structures of cooperation that people live inside but rarely see.

My hope is that by making those structures visible, we can build systems — social, organisational, civic, and technical — that remain open, generative, and capable of supporting us rather than consuming us.